Hindi versus Urdu are often presented as two distinct languages standing in opposition to each other. However, from a historical and linguistic perspective, they originate from the same base and evolved together for centuries before being consciously separated. Both languages developed from a form of Indo-Aryan speech commonly referred to as Hindustani, which emerged in North India through sustained interaction between local dialects such as Khari Boli and external linguistic influences brought by traders, settlers, and rulers.

In the medieval period, particularly during the Delhi Sultanate and Mughal rule, people from different regions, religions, and social backgrounds needed a common language for communication. This necessity gave rise to a shared spoken language that combined local Indo-Aryan dialects with vocabulary from Persian, Arabic, and Turkish. At this stage, there was no concept of Hindi versus Urdu. The language was fluid, functional, and inclusive.

- Hindi versus Urdu: Script, Vocabulary, and Literary Traditions

- Hindi versus Urdu: Politics, Identity, and Contemporary Reality

- Hindustani: The Common Parent of Hindi and Urdu

- Hindi versus Urdu in Media and Journalism

- The Future of Hindi versus Urdu in a Globalized World

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

The idea of Hindi versus Urdu began to take shape much later, especially during the nineteenth century under British colonial rule. Colonial administrators sought to classify Indian society into neat categories, including language. This process encouraged the separation of Hindustani into two standardized forms. Hindi was increasingly associated with Sanskrit vocabulary and the Devanagari script, while Urdu was linked with Persian-Arabic vocabulary and the Perso-Arabic script.

This deliberate standardization transformed a shared language into two perceived linguistic identities. The framing of Hindi versus Urdu was further intensified by emerging religious and cultural nationalism. Hindi came to be linked with Hindu identity, and Urdu with Muslim identity, despite both being spoken across communities.

- Hindi versus Urdu: Script, Vocabulary, and Literary Traditions

- Hindi versus Urdu: Politics, Identity, and Contemporary Reality

- Hindustani: The Common Parent of Hindi and Urdu

- Hindi versus Urdu in Media and Journalism

- The Future of Hindi versus Urdu in a Globalized World

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Hindi versus Urdu: Script, Vocabulary, and Literary Traditions

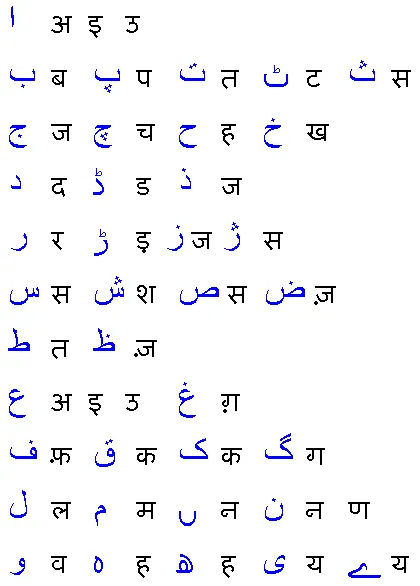

One of the most visible aspects of Hindi versus Urdu lies in the difference between their scripts. Hindi is written in the Devanagari script, while Urdu uses a modified Perso-Arabic script written in the Nastaʿlīq style. This visual distinction often reinforces the perception that Hindi versus Urdu are entirely different languages, even when their spoken forms remain largely the same.

Scripts are not merely tools for writing; they carry cultural and historical significance. In the context of Hindi versus Urdu, script choice became a marker of identity. Devanagari connected Hindi to Sanskrit texts, Hindu religious literature, and ancient Indian philosophy. The Perso-Arabic script connected Urdu to Persian poetry, Islamic scholarship, and Central Asian literary traditions.

Vocabulary further deepens the apparent divide in Hindi versus Urdu. Modern standardized Hindi draws heavily from Sanskrit, particularly for academic, technical, and official terms. Urdu, on the other hand, incorporates a significant number of Persian and Arabic words for similar purposes. As a result, formal Hindi and formal Urdu can sound quite different, even though everyday speech remains similar.

The literary traditions associated with Hindi versus Urdu also reflect these influences. Urdu literature is especially known for its poetic forms such as ghazals and nazms, characterized by emotional intensity and refined expression. Hindi literature, influenced by Sanskrit traditions, includes devotional poetry, epic narratives, and modern social realism.

Despite these distinctions, the boundaries between Hindi and Urdu literature have never been absolute. Many writers and poets freely used elements from both traditions. In popular culture, especially cinema and music, the blending of Hindi and Urdu vocabulary is common, demonstrating that Hindi versus Urdu often coexist rather than compete.

Hindi versus Urdu: Politics, Identity, and Contemporary Reality

The modern perception of Hindi versus Urdu cannot be separated from politics and identity formation, particularly during the twentieth century. As nationalist movements gained strength, language became a symbol of cultural assertion. Hindi was promoted as a national language in India, while Urdu became increasingly associated with Muslim identity and later with Pakistan.

This political framing intensified the idea of Hindi versus Urdu as opposing forces. Educational policies, administrative practices, and language movements reinforced this separation. Urdu, despite being widely spoken, faced marginalization in many regions, while Hindi gained institutional dominance.

However, everyday linguistic reality challenges the narrative of Hindi versus Urdu as a strict divide. In daily conversation, people often speak a hybrid form that blends both languages naturally. Popular media, cinema, and music continue to use this shared linguistic space, reaching audiences who understand both without conscious effort.

This living form of language demonstrates that Hindi versus Urdu is more about perception than practice. Most speakers are unaware of whether a word comes from Sanskrit or Persian. What matters is communication, emotion, and connection.

In recent years, scholars and educators have increasingly emphasized the shared heritage behind Hindi versus Urdu. This approach encourages linguistic harmony and cultural understanding, moving beyond rigid classifications.

Ultimately, Hindi versus Urdu is not a conflict rooted in language itself. It is a reflection of historical, political, and social influences imposed on a shared linguistic tradition. When viewed without ideological bias, Hindi and Urdu emerge not as rivals, but as complementary expressions of a common cultural and communicative legacy.

Hindustani: The Common Parent of Hindi and Urdu

The discussion of Hindi versus Urdu often begins with the assumption that they are fundamentally different languages. However, a closer linguistic and historical examination reveals that both Hindi and Urdu originate from the same parent language commonly referred to as Hindustani. Understanding Hindustani as the common foundation is essential to dismantling the misconception that Hindi versus Urdu represents a natural or inevitable divide.

Hindustani developed in North India as a practical spoken language used by people from diverse social, religious, and cultural backgrounds. It emerged from Indo-Aryan dialects, particularly Khari Boli, and gradually absorbed influences from Persian, Arabic, and Turkish due to centuries of trade, migration, and governance. The purpose of Hindustani was not literary sophistication or religious symbolism, but communication. It allowed people to interact across communities without linguistic barriers.

For several centuries, Hindustani functioned as a shared spoken language without rigid classification. Poets, traders, soldiers, and ordinary citizens used it freely, borrowing words from multiple linguistic sources without concern for purity. During this period, the idea of Hindi versus Urdu did not exist. Language use was organic, flexible, and responsive to social needs rather than ideological boundaries.

The distinction between Hindi and Urdu emerged much later, particularly during the colonial period. British administrators, in their attempt to categorize Indian society, encouraged linguistic standardization. Hindustani was gradually split into two formal registers. Hindi was promoted with a stronger emphasis on Sanskrit-derived vocabulary and written in the Devanagari script. Urdu, on the other hand, retained Persian and Arabic influences and adopted the Perso-Arabic script. This division marked the beginning of the conceptual framework of Hindi versus Urdu.

Despite this formal separation, the spoken form of the language remained largely unchanged. Everyday conversation continued to reflect Hindustani rather than strictly Hindi or strictly Urdu. Grammar, sentence structure, verb forms, and basic vocabulary remained almost identical. A speaker using simple, conversational language could be understood by both Hindi and Urdu speakers without difficulty. This mutual intelligibility highlights the shared parentage of the two languages.

The persistence of Hindustani in daily life challenges the narrative of Hindi versus Urdu as opposing linguistic systems. In markets, homes, cinema, and popular music, people continue to speak a blended form that draws from both traditions. This living language ignores script-based and vocabulary-based divisions imposed by formal institutions.

Recognizing Hindustani as the common parent of Hindi and Urdu shifts the discussion from conflict to continuity. It reveals that the divide between Hindi versus Urdu is not rooted in language itself, but in historical, political, and cultural forces that shaped how the language was categorized and represented.

In essence, Hindustani serves as a reminder that languages evolve to connect people, not divide them. Hindi and Urdu, as standardized forms, represent different stylistic and cultural expressions of the same linguistic core. Understanding this shared origin allows for a more inclusive and accurate perspective on Hindi versus Urdu, emphasizing unity over opposition and communication over classification.

Hindi versus Urdu in Media and Journalism

The discussion of Hindi versus Urdu takes on a particularly important dimension in the field of media and journalism. News media does not merely report events; it shapes public opinion, cultural identity, and linguistic preferences. The way Hindi and Urdu are used in journalism reflects broader social, political, and institutional attitudes toward these languages.

Historically, both Hindi and Urdu played significant roles in print journalism in the Indian subcontinent. Early newspapers used a shared Hindustani register, making content accessible to a wide audience. However, as the distinction between Hindi and Urdu became more pronounced during the colonial period, media outlets began aligning themselves with specific linguistic identities. This marked a shift from inclusive communication to targeted linguistic representation, reinforcing the idea of Hindi versus Urdu as separate entities.

In contemporary media, Hindi dominates mainstream journalism in India. Most national television channels, newspapers, and digital platforms use standardized Hindi written in the Devanagari script. This form of Hindi often relies heavily on Sanskrit-derived vocabulary, particularly in political reporting, legal discussions, and formal news segments. While this promotes linguistic uniformity, it can also create accessibility barriers for audiences more familiar with colloquial Hindustani or Urdu-influenced speech.

Urdu journalism, on the other hand, occupies a more marginalized space despite its historical richness. Urdu newspapers, magazines, and digital platforms continue to exist, but their reach is limited compared to Hindi media. In many regions, Urdu journalism struggles with institutional neglect, lack of funding, and reduced visibility. This imbalance strengthens the perception of Hindi versus Urdu as a hierarchy rather than a parallel linguistic tradition.

Language choice in journalism also affects tone and emotional resonance. Urdu journalism is often noted for its expressive style, metaphorical richness, and emotional depth, especially in editorials and opinion pieces. Hindi journalism, particularly in its formal register, tends to adopt a more direct, administrative tone. These stylistic differences influence how stories are perceived and remembered by audiences.

Broadcast media presents an interesting contrast. Television news debates and radio programs often rely on a blended spoken language that closely resembles Hindustani. Anchors and reporters frequently mix Hindi and Urdu vocabulary to ensure clarity and reach. This spoken reality challenges the rigid divide of Hindi versus Urdu seen in print media and official language policies.

Digital journalism has further blurred the boundaries. Online platforms, social media, and independent news portals increasingly prioritize accessibility over linguistic purity. Writers often adopt a mixed register to engage diverse audiences, reflecting how people actually speak and understand language. This shift suggests that the future of Hindi versus Urdu in journalism may be more integrative than divisive.

However, the politics of language remains influential. Editorial choices, script usage, and vocabulary selection are often shaped by ideological considerations. In this context, Hindi versus Urdu becomes less about communication and more about representation, power, and identity.

In conclusion, Hindi versus Urdu in media and journalism reflects broader societal dynamics rather than linguistic necessity. While institutional journalism often reinforces separation, everyday media consumption tells a different story. Spoken language, digital platforms, and popular content continue to bridge the gap, proving that effective journalism depends not on rigid linguistic labels but on clarity, inclusivity, and audience connection.

The Future of Hindi versus Urdu in a Globalized World

The discussion of Hindi versus Urdu in a globalized world requires moving beyond historical divisions and examining how language adapts to changing social, technological, and cultural realities. Globalization has transformed how languages are spoken, taught, consumed, and preserved. In this context, the future of Hindi versus Urdu is shaped less by rigid linguistic boundaries and more by mobility, media, and digital communication.

Globalization encourages interaction across borders, cultures, and communities. Hindi and Urdu speakers today are not confined to South Asia. Large diaspora communities in the Middle East, Europe, North America, and Australia continue to use these languages in daily life. In these spaces, the distinction between Hindi versus Urdu often becomes less rigid. Speakers prioritize mutual understanding over script, vocabulary origin, or formal classification. A blended form of Hindustani is commonly used, reflecting practical communication rather than ideological preference.

Technology plays a crucial role in reshaping the future of Hindi versus Urdu. Social media platforms, streaming services, and digital news outlets encourage informal, conversational language. Users frequently mix Hindi and Urdu vocabulary, often writing in Roman script rather than traditional scripts. This shift reduces the importance of script-based distinctions and allows language to function more as a shared communicative tool. In digital spaces, linguistic purity holds little value compared to reach, relatability, and clarity.

Popular culture further influences this evolution. Cinema, music, web series, and online content increasingly rely on a hybrid linguistic register that resonates with diverse audiences. The success of such content demonstrates that audiences are more receptive to inclusive language than to rigid categorizations. This trend challenges the traditional narrative of Hindi versus Urdu as separate and competing entities.

Education systems, however, remain a critical factor in determining the future trajectory of Hindi versus Urdu. While Hindi continues to enjoy institutional support in India, Urdu often faces limited representation despite its cultural significance. Globalization offers both a challenge and an opportunity here. On one hand, dominant languages risk overshadowing minority languages. On the other hand, global academic interest, online learning platforms, and cultural exchange programs provide new avenues for the preservation and promotion of Urdu alongside Hindi.

Another important aspect is identity in a globalized world. Younger generations increasingly view language as a personal and cultural resource rather than a fixed marker of religious or national identity. For them, Hindi versus Urdu is less about opposition and more about expression. This shift in perception weakens traditional ideological divides and encourages linguistic coexistence.

At the same time, political narratives continue to influence language discourse. Efforts to promote linguistic nationalism can reinforce divisions and affect policy decisions related to education, media, and public usage. The future of Hindi versus Urdu will therefore depend on whether societies choose inclusivity or exclusivity in their language policies.

In conclusion, the future of Hindi versus Urdu in a globalized world is not predetermined. While historical and political forces have emphasized division, contemporary realities point toward convergence. Digital communication, diaspora interactions, and popular culture are reshaping how these languages are used and understood. If allowed to evolve naturally, Hindi and Urdu are likely to continue functioning as interconnected expressions of a shared linguistic heritage, proving that in a globalized world, communication matters more than classification.

Conclusion

The discussion of Hindi versus Urdu is often misunderstood as a linguistic conflict, when in reality it reflects a shared history shaped by cultural exchange, political influence, and evolving identities. Throughout this blog, it becomes evident that Hindi and Urdu originate from the same linguistic foundation and continue to share grammatical structure, everyday vocabulary, and mutual intelligibility. Their perceived division arises not from language itself, but from historical processes that emphasized difference over commonality.

The examination of Hindustani as their common parent highlights how natural language development prioritizes communication rather than classification. Differences in script, vocabulary, and literary tradition, while significant, represent stylistic and cultural choices rather than structural separation. Media, journalism, and popular culture further demonstrate that in practical usage, Hindi and Urdu often function together rather than apart.

In a globalized world, the rigid framing of Hindi versus Urdu becomes increasingly irrelevant. Digital platforms, diaspora communities, and evolving attitudes toward identity encourage linguistic blending and inclusivity. These developments suggest that the future of Hindi and Urdu lies not in opposition, but in coexistence and mutual enrichment.

Ultimately, understanding Hindi versus Urdu as interconnected languages allows for a more balanced and informed perspective. Recognizing their shared heritage fosters cultural harmony and reminds us that languages are living systems, shaped by people, history, and context. When freed from ideological boundaries, Hindi and Urdu continue to serve their most essential purpose: connecting individuals through expression, emotion, and shared human experience.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the main difference between Hindi and Urdu?

The main difference between Hindi and Urdu lies in their scripts and formal vocabulary. Hindi uses the Devanagari script and draws heavily from Sanskrit, while Urdu uses the Perso-Arabic script and incorporates more Persian and Arabic vocabulary. Structurally and grammatically, both languages are very similar.

2. Are Hindi and Urdu separate languages or the same language?

Linguistically, Hindi and Urdu are considered two standardized forms of the same base language, Hindustani. They are often treated as separate languages for cultural, political, and literary reasons rather than structural ones.

3. Can Hindi and Urdu speakers understand each other?

Yes, Hindi and Urdu speakers can usually understand each other in everyday conversation. Mutual intelligibility is high as long as the language remains conversational and avoids heavily formal or literary vocabulary.

4. Why did Hindi and Urdu become associated with religion?

Hindi and Urdu became linked with religious identity during the colonial period and nationalist movements. Hindi was associated with Hindu identity and Urdu with Muslim identity, even though both languages were historically spoken across communities.

5. What role did the British play in the Hindi versus Urdu divide?

British colonial administration encouraged linguistic classification and standardization. This process contributed to the formal separation of Hindustani into Hindi and Urdu, reinforcing social and political divisions.

6. What is Hindustani, and how is it related to Hindi and Urdu?

Hindustani is the common spoken ancestor of both Hindi and Urdu. It developed as a practical language for communication and remains the basis of everyday speech used across North India and in popular culture.

7. Why does Hindi sound different from Urdu in news and official communication?

In formal settings, Hindi uses more Sanskrit-derived terms, while Urdu relies on Persian and Arabic vocabulary. This makes formal Hindi and formal Urdu sound quite different despite their shared grammatical structure.

8. Is Urdu declining in modern India?

Urdu faces institutional challenges and reduced representation in education and media, but it continues to thrive in literature, poetry, journalism, and digital spaces. Revival efforts and online platforms are helping sustain its presence.

9. How does popular culture affect Hindi versus Urdu?

Films, music, and digital media often use a blended form of Hindi and Urdu. This reflects real-world usage and helps bridge the perceived divide between the two languages.

10. What is the future of Hindi versus Urdu?

The future of Hindi versus Urdu points toward coexistence rather than conflict. Globalization, digital communication, and changing attitudes toward identity are encouraging a more inclusive and blended linguistic approach.

Comments