Published by Enthuziastic

Hello chess friends! Welcome back to Enthuziastic. You know, one of the most common questions I get from students and parents alike is simply this: "Sir, how many moves should I memorise?" or "Madam, I learnt the Sicilian Dragon, but my opponent played something else on move 4, and I lost badly. What to do?"

It is a genuine struggle, isn’t it? You sit down with a book or a video course, you spend hours mugging up variations, and then you go to the tournament hall. You are all ready to play your 20 moves of preparation. But then, your opponent plays a weird pawn move you have never seen. Suddenly, all that memorisation goes out the window, and you are left scratching your head.

The problem is not that you didn't study enough. The problem is often how you studied. In chess, especially in the opening phase, there is a constant battle between memorisation (rote learning) and understanding (knowing the concepts). If you only memorise, you are like a parrot you can repeat what you heard, but you cannot have a conversation. If you only rely on general understanding without knowing any theory, you might fall into a trap before the game even properly starts.

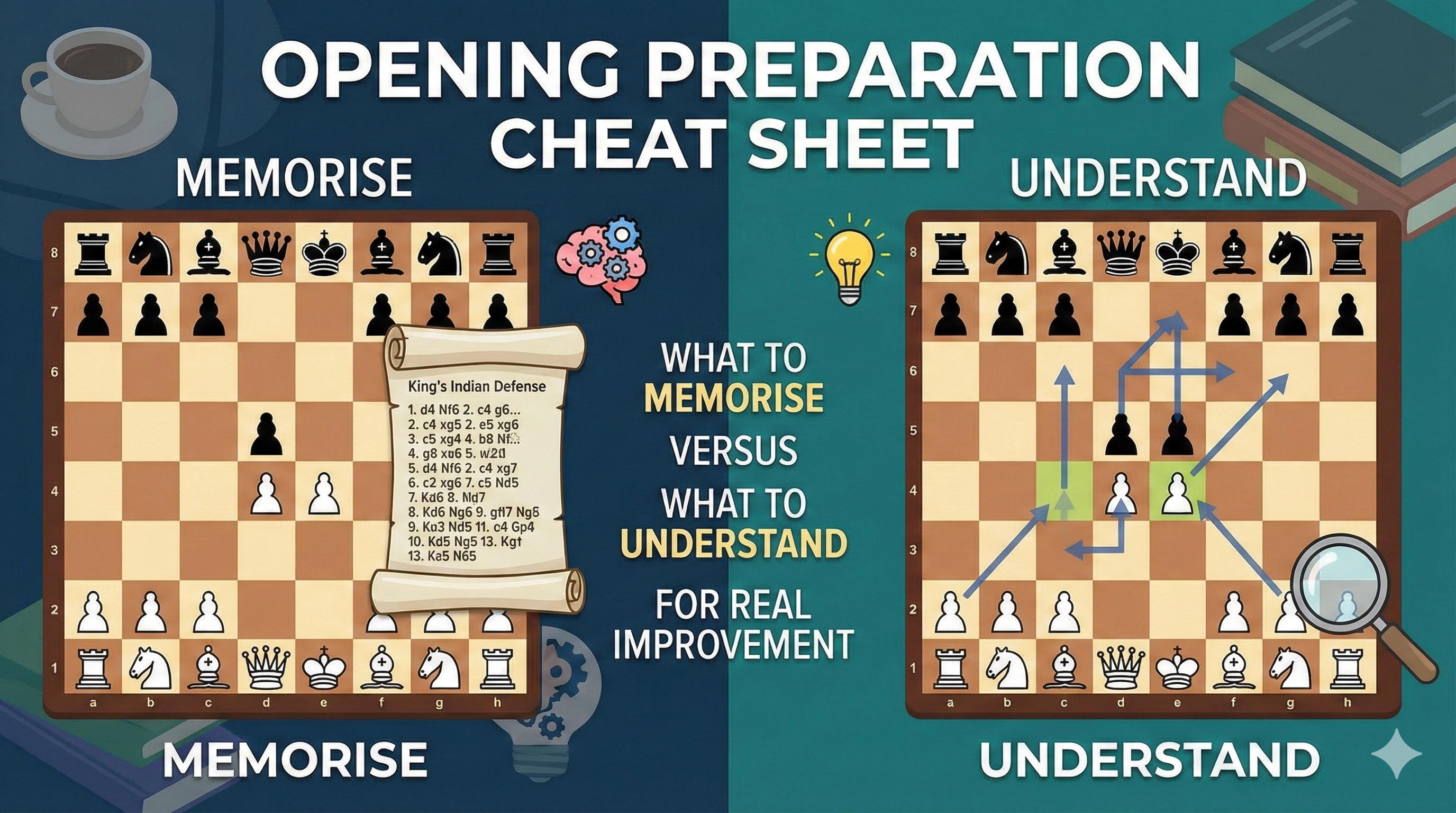

In this blog, we are going to break down this "Opening Preparation Cheat Sheet." We will look at exactly what you need to lock into your memory, what you need to understand with your logic, and how to balance the two so you can play confident, strong chess. Whether you are a beginner just learning the Italian Game or an advanced player grinding the Grünfeld, this guide is for you.

Let’s dive in!

Introduction to opening preparation

First things first, let’s talk about why we even bother with opening preparation. Many players, especially in India where we love our tactical complications, sometimes feel that "real chess" only starts in the middlegame. They think, "I will just play natural moves, control the centre, and then outplay him later."

While that is a noble thought, in modern chess, it is a bit risky.

Why proper opening preparation matters

Imagine you are writing an exam. If you already know the answers to the first 10 questions because you studied them yesterday, how much time do you save? A lot, right? And how confident do you feel? Very confident.

Opening preparation does the same thing for your chess game:

It saves you time on the clock: If you know the first 15 moves, you can play them in 2 minutes. Your opponent might spend 20 minutes finding the same moves. That gives you a huge time advantage for the complicated middlegame.

It keeps you safe: There are thousands of traps in the opening. If you don't know them, you might lose a piece on move 7. Preparation ensures you don't accidentally lose immediately.

It gives you a psychological edge: When you play your moves quickly and confidently, your opponent starts to get nervous. They think, "Oh no, he knows everything! I am walking into his preparation."

The big confusion: memory vs. logic

The biggest mistake players make is thinking they have to memorise everything. You cannot. Computers can memorise millions of lines; humans cannot. We have jobs, schools, families, and other hobbies.

If you try to memorise every single variation of the Ruy Lopez, you will go crazy. And worse, you will forget it all under pressure. The secret to real improvement is knowing which specific parts to memorise and which vast areas to just understand.

What to memorise in chess openings

Okay, so let’s start with the hard work. Yes, you have to memorise some things. You cannot purely "guess" your way through a sharp opening. But you should be very selective about what you store in your brain's hard drive.

Think of memorisation as your safety kit. You only pack the essentials that will keep you alive.

1. Forcing lines and "only moves"

This is the most critical category. In chess, a "forcing line" is a sequence of moves where you have no choice. If you don't play the exact right move, you lose.

For example, in the Botvinnik Variation of the Semi-Slav, the game gets incredibly wild. Pieces are hanging, pawns are promoting early, and kings are running around. In such positions, you cannot sit at the board and figure it out. It is too complex. You must memorise the moves.

Cheat Sheet Rule: If a position is sharp, tactical, and one wrong step leads to a checkmate or loss of material, memorise it. Do not rely on your intuition here.

2. Opening traps (for and against you)

You need to memorise standard traps, not just to catch your opponent, but to avoid falling into them yourself.

Take the Legal’s Mate or the Fishing Pole Trap. These are specific patterns. If you see the setup, you shouldn't have to calculate "If I take the knight, he moves the queen..." No. You should instantly recognise the pattern from memory.

To avoid: You must memorise the specific move orders that allow your opponent to trap you. For instance, in the Queen's Gambit Declined, you must know when it is safe to develop your bishop and when it gets trapped.

To execute: If your opponent makes a mistake, you should know the punishment immediately.

3. The "main line" foundation

Every opening has a "Main Line." This is the path most often travelled by Grandmasters. You should memorise the first 7-10 moves of your main opening repertoire.

Why? because these moves are played most frequently. If you play 1.e4, you will see 1...e5 very often. You should know your response (2.Nf3, 2.Bc4, etc.) automatically. You shouldn't be wasting energy thinking about move 2 or 3.

4. Transpositions (move orders)

This is a bit advanced, but very important. Sometimes, you can reach the same position via different move orders.

Example: You can reach a French Defense structure from a Sicilian opening sometimes.

What to memorise: You need to remember which move order avoids your opponent's best options. "If I play the knight out first, he can pin me. But if I play the pawn first, I stop the pin." These small nuances must be memorised.

Practical tips to memorise efficiently

Now, I know what you are thinking. "But sir, how do I remember all this?" Here are some tips that work well for our students at Enthuziastic:

Chunking: Don't try to learn 20 moves at once. Learn them in chunks of 3-4 moves. "First I control the centre, then I develop knights, then I castle."

The "Why" Check: Even when memorising, ask "Why?" If you can’t explain why a move is played, you will forget it.

Don't Overload: Do not try to learn 5 new openings in a week. Stick to one. Master the main line first before looking at the side lines.

What to understand in opening study

Now comes the fun part. This is where you actually learn to play chess, not just recite moves. Understanding is what saves you when your memory fails. It is the fluid intelligence of your game.

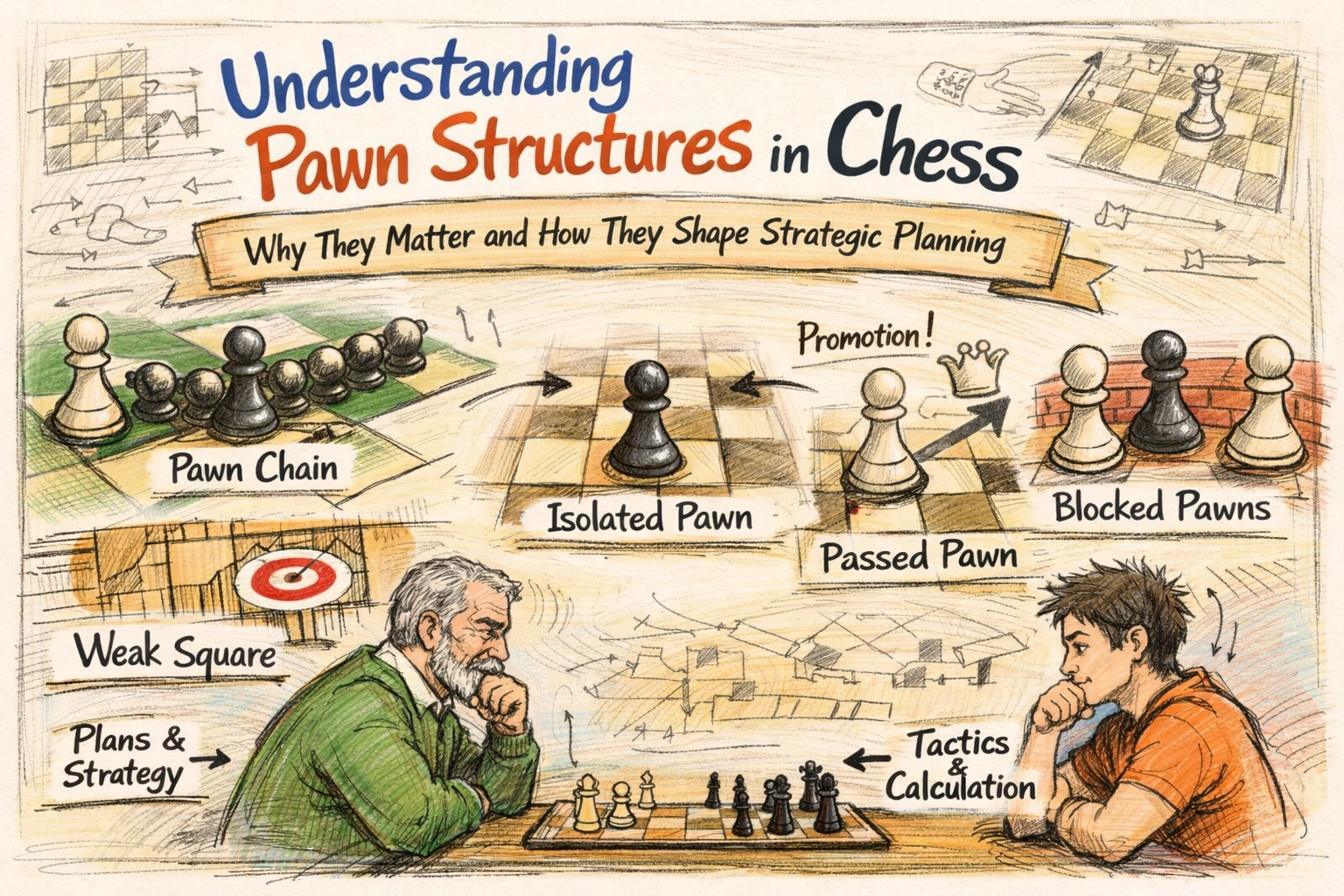

1. The "soul" of the opening: pawn structures

Philidor famous said, "Pawns are the soul of chess." This is 100% true for openings.

You don't need to memorise where the Knight goes in every variation of the Caro-Kann. You need to understand the Pawn Structure.

Isolanis (Isolated Queen Pawn): If your opening leads to an IQP, you must understand the plans: attack in the middlegame, avoid trading pieces.

Closed Chains: If you play the French Defense, you must understand the locked pawn chain (d4-e5 vs d5-e6) and how to break it with ...c5 or ...f6.

King’s Indian Structure: You must understand that White attacks on the Queen’s side and Black attacks on the King’s side.

Cheat Sheet Rule: If you know the pawn structure, you can find the right plan even if you have never seen the position before.

2. Typical piece placements

Instead of memorising "Bishop to d3 on move 6," understand where the pieces belong.

In the London System, the dark-squared bishop almost always goes to f4. The light-squared bishop goes to d3. The knights go to f3 and d2.

Once you understand this "setup," you can play the moves in almost any order. You are playing by concept, not by rote memory.

3. Key strategic plans

What is the goal of your opening?

Italian Game: The goal is usually to control the centre and attack f7 or prepare a slow build-up with c3 and d3.

Sicilian Defense: The goal for Black is to counter-attack and create imbalances.

If you simply memorise moves without knowing the goal, you will reach move 15 and have a great position, but absolutely no idea what to do next. You will just shuffle pieces back and forth until you lose.

Understanding means knowing the plan: "Okay, out of the opening, I need to launch a minority attack on the queenside."

4. The "good" and "bad" pieces

Every opening tends to create specific "problem pieces."

French Defense: Black’s light-squared bishop is often "bad" (blocked by pawns). The whole game revolves around trying to free this bishop or trade it off.

King’s Indian: White’s dark-squared bishop can be a monster.

Understanding which pieces you want to keep and which you want to trade is far more valuable than memorising move 12 of a sideline.

Real examples: understanding wins over memory

Let me tell you a story about a student. He was playing a tournament game. He had memorised a very sharp line against the Sicilian. But his opponent, an older uncle who had been playing for 30 years, played a very strange, passive move on move 5.

The student panicked. "This wasn't in the database!"

But then he paused and used his understanding.

He looked at the board: "Okay, he has moved his pawn to h6. It does nothing for the centre. It doesn't develop a piece. So, I have a lead in development. What is the principle? Open the centre!"

The student played d4 immediately, blasted open the position, and won in 20 moves. He didn't win because he memorised that line; he won because he understood the principle: Punish passive play with central activity.

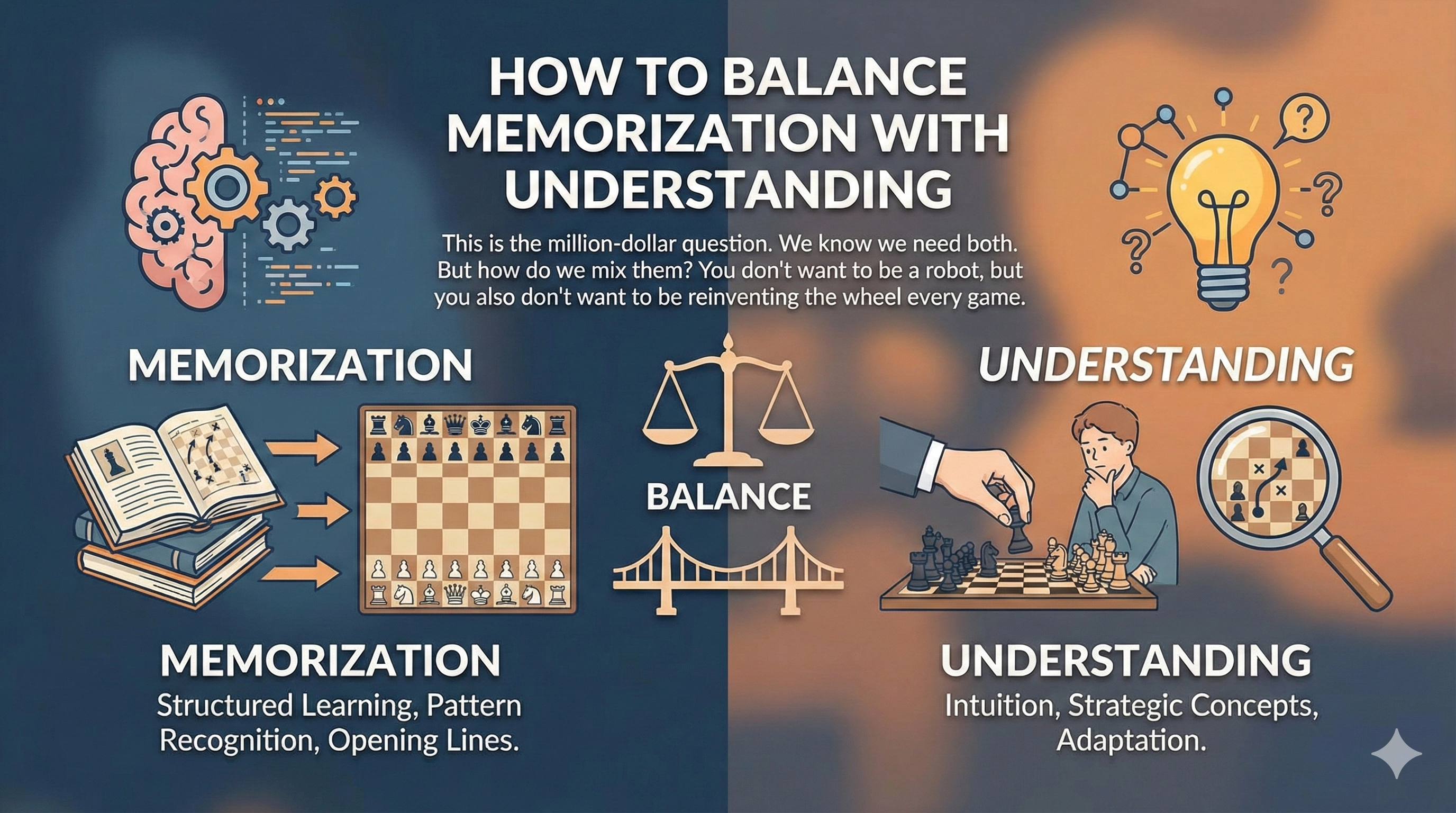

How to balance memorisation with understanding

This is the million-dollar question. We know we need both. But how do we mix them? You don't want to be a robot, but you also don't want to be reinventing the wheel every game.

The tree of knowledge analogy

Think of your opening repertoire like a tree.

The Trunk (Understanding): This is the core concept. "I play the King's Indian because I like attacking the King." This never changes.

The Big Branches (Main Lines): These you must memorise. They are the sturdy paths that support everything else.

The Leaves (Sidelines): These are the thousands of variations. You cannot memorise all the leaves. You just need to know generally where they grow (understanding).

Practical routine: the 20/80 rule

For most players (below Master level), your study time should be:

20% Memorisation: Drilling exact move orders, checking your lines in Chessable or a database.

80% Understanding: Watching videos about the plans, analyzing master games, and looking at pawn structures.

Don't Flip It! Many beginners do 80% memorisation and 20% understanding. That is why they get stuck at 1200 ELO.

How to avoid "blind memorisation" traps

Have you ever seen a player blitz out 15 moves, look super confident, and then on move 16 hang a Queen? That is blind memorisation. They were on "autopilot."

The Fix:

When you study a line, talk to yourself. Literally, speak out loud (or in your head).

"I am moving the Knight here because it attacks e4."

"I am pushing h3 to prevent his Bishop coming to g4."

By attaching a "reason" to the "move," you are linking Memory with Logic. If you forget the move, the logic might help you find it again.

Transitioning from opening to middlegame

The scariest moment is when your "book knowledge" ends. This is where understanding takes the baton from memory.

Checkpoint: When you run out of memorised moves, stop. Take a deep breath. Look at the pawn structure. Ask yourself: "What is my plan based on this structure?"

Do not just play the next move instantly because it "looks natural." Switch your brain from Recall Mode to Calculate Mode.

Training methods for structured improvement

Okay, so we have the theory. Now, how do we actually practice this at home? You can't just wish for better preparation; you have to work for it. Here is a training plan you can use.

1. The "model game" method

This is my favourite method for understanding.

Step 1: Choose your opening (e.g., The Ruy Lopez).

Step 2: Find 10 games played by Grandmasters who are experts in this opening (e.g., Caruana or Karpov).

Step 3: Play through the games quickly. Don't analyze deep variations. Just watch.

Step 4: Look for patterns. "Oh, look, in 7 out of 10 games, he moved the Rook to e1 and then pushed h3."

Result: You will naturally "absorb" the plans without painfully memorising them. Your brain is great at pattern recognition.

2. Spaced repetition for memorisation

For the lines you do need to memorise (the sharp stuff), use Spaced Repetition.

This means you review the line today. Then again tomorrow. Then in 3 days. Then in a week.

Tools like Chessable are built exactly for this. Or you can just use a physical board and a notebook.

The key: Do not cram. Doing 10 minutes every day is 100 times better than doing 2 hours once a week.

3. Analyze your own games (the reality check)

After every game you play online or offline, check the opening.

Did you follow your prep? If yes, great.

Where did you deviate? Did you forget the move? Or did you not know it?

Did you understand the resulting position? If you came out of the opening with a slight advantage but lost because you didn't know what to do, you need to study plans (Understanding), not more moves.

4. Use engines wisely (warning!)

Computers are dangerous for beginners. An engine might tell you that 12...Qb6 is the best move (+0.4 advantage). But if you don't understand why, that move is useless to you.

Only use the engine to check for tactical blunders (blundering a piece).

Do not use the engine to memorise lines that you don't understand. If the engine suggests a move that looks weird to you, try to find a human explanation (video or book) for it.

Developing your personalised plan

Every player is different.

Aggressive Players: You need more memorisation because you play sharp lines (Sicilian, King’s Indian). One slip and you are dead.

Positional Players: You need more understanding. You play safer openings (London, Caro-Kann) where ideas matter more than exact moves.

Action Item: Tonight, sit down and look at your repertoire. Are you an Attacker or a Defender? Adjust your study balance accordingly.

Conclusion

Chess is a beautiful game because it balances art (ideas) and science (calculation/memory). Opening preparation is not about becoming a computer. It is about building a safety net so you can express your ideas on the board.

Remember the cheatsheet:

Memorise: Forcing lines, sharp tactics, and your main "trunk" lines.

Understand: Pawn structures, piece placements, standard plans, and endgames.

Balance: Use your memory to save time, but use your understanding to navigate the unknown.

At Enthuziastic, we believe that every player has the potential to master their openings, not by rote learning like a robot, but by understanding the beautiful logic behind the moves. So, go ahead, clean up your repertoire, stop fearing the theory, and start enjoying the opening phase!

Good luck with your games, and may your openings always lead to winning middlegames!

FAQs: Opening preparation & study tips

1. How many openings should I learn as a beginner?

Keep it simple! As a beginner, stick to one opening for White (like the Italian Game or London System) and two for Black (one against 1.e4 and one against 1.d4). Trying to learn too many at once will just confuse you. Master one set before adding more.

2. I forget my preparation during the game. What should I do?

Don't panic! If you forget the specific move, fall back on Opening Principles: Control the centre, develop your pieces, castle early, and don't move the same piece twice. If you understand the general plan of your opening, you can usually find a decent move even if it's not the "book" move.

3. Is it better to study openings with books or videos?

It depends on your learning style. Videos are great for understanding the general ideas and plans because a coach explains the "why." Books (and tools like Chessable) are generally better for memorisation because you can go at your own pace and review specific lines repeatedly. A mix of both is usually best.

4. How much time should I spend on opening prep vs tactics?

For players below 1800 Elo, tactics are still king. You should spend about 20-30% of your time on openings and the rest on tactics, middlegame planning, and endgames. Don't become a "theory wizard" who drops pieces in the middlegame!

5. My opponent played a move I've never seen. How do I punish them?

First, check if it's a trap. If it looks safe, ask yourself: "What drawback does this move have?" Does it weaken a square? Does it neglect development? If it's a bad move, the punishment is usually simple: stick to basic principles. Develop rapidly and attack the weakness they created. You don't need a specific memorised punishment; logic is enough.

6. Should I use an engine to prepare openings?

Be careful. Engines show "0.00" or "+0.3" moves that are technically perfect but very hard for humans to play. Use engines to check for tactical blunders (making sure you don't lose immediately), but rely on Master games and books to learn the plans. Follow human logic, not computer logic.

7. What is a "Repertoire"?

A repertoire is simply your personal collection of openings that you play. It’s like your "playbook" in cricket or football. It implies that you have a prepared response for the most common moves your opponent might play. A good repertoire is consistent for example, playing sharp attacking openings with both White and Black.

8. How often should I update my openings?

You don't need to change openings often. In fact, sticking to one opening for years is better because you learn it deeply. "Update" your openings only when you find a line that gives you trouble in games, or if you feel you have completely outgrown the style of your current opening. Don't jump from the Sicilian to the French just because you lost one game!

Comments